Hyperinflation Generation

How Over 40 Million Children Speed-Ran Economic Collapse and Monetary Chaos in Summer 2025

“Dad, how are they going to fix the economy?” A few weeks ago, my twelve-year-old started complaining about “the economy” — not the American economy — the economy in Grow a Garden, the Roblox game that over the last several months became the dominant social experience for his generation.

“Dad, how are they going to fix it? Everyone is at least a quadrillionaire now. There are hardly any trillionaires anymore, and being a billionaire is just pathetic.”

Almost every parent with children between 5 and 13 years old has heard about this game—their child’s latest apparently harmless obsession. What few of them know and even fewer in the economics or finance profession (none as far as I can tell) noted, is that these children participated in the largest-ever sandboxed monetary economics experiment ever run. Almost no one without children in this age range knows anything about it.

As my son’s obsession with this game started early in the summer, we marveled at the staggering number of concurrent users and the reported total registered players. The game was only 72 days old at the time and working backwards I estimated the game had exceeded and was sustaining 10% daily growth from a substantial base. The viral coefficient was likely unprecedented.

My entrepreneurially-minded child was impressed by this and reported the rumors and drama surrounding its ownership. “Jandel bought a 50% stake from the creator who is a teenager! Then he paid a streamer $25k to broadcast it and got 1 million additional users! That was the BEST BUSINESS DEAL EVER!!!”

At first it seemed this growth would continue until every single kid was growing a garden. The game was achieving new milestones week after week, besting records set by Fortnite and others. Then came this talk about “the economy.” In the span of a couple months, my son witnessed the complete collapse of a monetary system, watched wealth inequality explode through currency debasement, and observed the social dynamics that emerge when money becomes meaningless. I understood he was describing, with casual precision, the endgame of unlimited money printing—something most economics textbooks only hint at in theoretical terms.

What makes this remarkable isn’t just that a child grasped these concepts, but the scale at which this education is occurring. Grow a Garden regularly hosts over 20 million concurrent players on weekends. For a sense of scale in terms of attention, this is only eclipsed by events like the Super Bowl, World Cup Soccer, the Emmys or the 2024 US Presidential Debate. In terms of economics, multi-player video games like World of Warcraft and EVE Online created sophisticated virtual economies studied by economists. Those games targeted adults with millions of total players but far smaller concurrent populations.

The timing feels almost prophetic. As the Federal Reserve continues to manipulate its balance sheet and the administration moves to accumulate bitcoin and place dovish appointees on the Fed board, tens of millions American children are discovering why sound money matters. They’re not learning it from textbooks—they’re living it.

The Anatomy of Digital Collapse

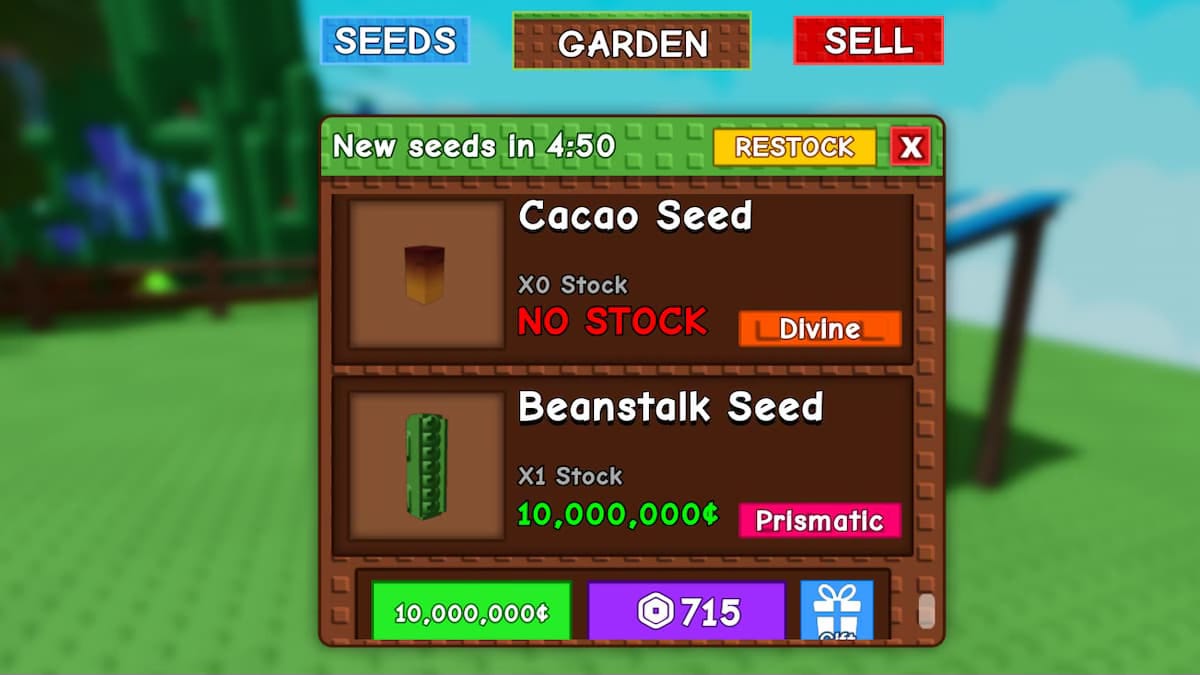

The mechanics of Grow a Garden’s hyperinflation mirror historical currency collapses with startling precision. Players plant seeds, grow fruits, and sell them for “shekels”—the game’s primary currency. Before the collapse, a trillion shekels represented substantial wealth. Then came what my son calls “the duping glitch.”

During the Culinary Update, a pet called a raccoon could duplicate expensive fruits directly from other players’ trees while leaving the original intact. The exploit was primarily utilized by YouTubers with access to plants worth quadrillions of shekels each. These content creators became the game’s equivalent of those with privileged access to the money printer—they could generate unlimited currency by selling duplicated fruits to the game’s automatic purchasing system.

Within three days, the effects rippled through the entire economy. The currency became worthless not because the underlying game mechanics changed, but because trust in the monetary system evaporated overnight.

This pattern has played out repeatedly throughout history. In Weimar Germany, those closest to the printing press—banks, government contractors, speculators—could convert new marks into real assets before prices adjusted. Ordinary citizens holding cash or fixed-income investments watched their savings become worthless. The social fabric tore as traditional concepts of fairness and reward for productive work disappeared.

My son experienced this firsthand. Despite not exploiting the duping glitch himself, he found himself with 20 quadrillion shekels simply through normal trading activity. “I kept trading and got more shekels,” he explained, “but then I looked around and everybody had quadrillions.” The psychological impact was immediate: if everyone has unlimited money, money has no meaning.

The Emergence of Parallel Systems

As shekels lost credibility, players spontaneously developed alternative value systems—exactly as populations do during real hyperinflation. Rare, non-duplicable items became the new store of value. “Admin seeds” that couldn’t be exploited by raccoons commanded premium prices. Ultra-rare items like “lemons”—created during a three-hour administrative prank—became digital gold, with only three or four existing in the entire game.

The parallels to hyperinflation-era behaviors are striking. Players moved their most valuable assets to private servers, accessible only to trusted friends. This mirrors how wealth flees to offshore havens during currency crises. Meanwhile, regular players in public servers engage in a parody of charity—handing out quadrillions of worthless shekels to prevent poor players from “spamming and begging” in chat.

The game developers attempted their own version of monetary reform. They introduced “Garden Coins,” a new currency that players could obtain by “ascending”—converting shekels at progressively worse exchange rates. The first conversion cost one trillion shekels for ten Garden Coins. The next cost five trillion, then seven trillion, then ten trillion. Each transaction made the next one more expensive, creating a deflationary spiral in reverse.

This system initially reset all player shekels, regardless of how many they possessed—a confiscatory monetary reset that destroyed even more wealth. Players who had accumulated septillions of shekels lost everything without warning. The developers later modified the system after massive player outrage, but the damage to trust was permanent.

Lessons from Digital Weimar

The behavioral adaptations my son described match documented responses to historical hyperinflations with unsettling accuracy. Players shifted from productive activity (growing plants) to speculation and arbitrage. They hoarded real assets while spending worthless currency as quickly as possible. Social hierarchies based on merit collapsed, replaced by those based on proximity to the money creation mechanism.

Perhaps most telling was the emergence of platform arbitrage. Players discovered they could buy Robux (the premium currency purchasable with real dollars) more cheaply on PC than on other platforms—500 units for $5 versus 400 units elsewhere. Sophisticated players exploited this pricing inefficiency, much as currency traders profit from central bank interventions during real monetary crises.

The game lost its sense of purpose. With no meaningful concept of winning and leaderboards rendered meaningless by incomprehensible wealth disparities, players began abandoning the platform. “People say it’s boring because it’s not the most popular game anymore,” my son explained. Competitors with clear victory conditions and stable economies began attracting players away from the hyperinflationary chaos.

The Generational Implication

The scale of this education is unprecedented. Tens of millions of children have now experienced hyperinflation not as an abstract concept but as lived reality. They understand viscerally that currencies can collapse, that proximity to money creation determines winners and losers, and that monetary authorities’ interventions often make problems worse.

These children are developing what Austrian economists call “monetary intuition” through direct experience rather than theory. They’ve seen how unlimited money printing destroys incentive structures. They’ve watched merit-based systems collapse into speculation and rent-seeking. They’ve learned that new currencies introduced to fix broken ones often carry their own problems.

When these children reach voting age, they will encounter economic policies through a lens shaped by this experience. Arguments about “necessary” monetary expansion or “temporary” emergency measures will be evaluated by individuals who have seen such policies play out in accelerated time. They’ve witnessed the social consequences of monetary debasement and the emergence of alternative value systems when official currency fails.

The implications extend beyond monetary policy. These children have learned that complex systems can fail rapidly and unexpectedly, that authorities don’t always have solutions to the problems they create, and that individuals must develop their own strategies for preserving wealth and value when institutions prove unreliable.

When we enter a period where the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet once again swells and political pressure for more aggressive monetary intervention grows, an entire generation has been inadvertently prepared for what may come next. They’ve experienced the complete lifecycle of a currency collapse and recovery attempt, compressed into months rather than years.

Whether this proves prescient or merely coincidental, one thing is certain: the next monetary crisis will unfold in front of the most economically educated generation of children in American history. They may be the first generation to recognize the early warning signs not from textbooks, but from their own lived experience of watching tens of millions of their peers discover that money, like the emperor’s clothes, has no inherent value beyond collective belief.

That recognition could prove to be the most valuable lesson of all.

Observing this we tend to think “Isn’t that cute, those children act just like adults!” As economic actors, they are indeed acting like adults because we have the same basic makeup, however, it may be more useful or instructive to observe how we adults act just like them. Adults have games too and it is useful framing to think of currency regimes as a game.

The dollar is a game. So is bitcoin. Each has its own game mechanics. Each is fun or rewarding in its way. Each is full of clueless newbs and experienced players. The dollar has fumbling admins just like Grow a Garden. The “admins” are called the Federal Reserve. When the admins of Grow a Garden screw up, the children disengage and find other games more fun. So it can be with adults and the dollar.

The Bitcoin Game

Understanding this dynamic helps explain Bitcoin’s appeal to those who recognize the dollar game’s limitations. Bitcoin operates by different rules—rules that reward long-term thinking over immediate consumption, productive contribution over financial engineering, and genuine scarcity over unlimited supply expansion.

The game mechanics are straightforward: provide goods or services to the world, receive Bitcoin in exchange, then demonstrate the discipline to hold rather than spend. Unlike dollars, which incentivize velocity and punish saving through inflation, Bitcoin’s fixed supply schedule rewards patience. The longer you maintain the posture of “I need nothing right now,” the more the network rewards your restraint. It’s a positive-sum game where everyone who exercises discipline benefits everyone else who does the same.

Most importantly, Bitcoin remains voluntary. Unlike national currencies backed by legal tender laws and taxation, Bitcoin’s only enforcement mechanism is attractiveness. Players can leave at any time—though as my son learned in Grow a Garden, once you understand superior game mechanics, it becomes difficult to return to systems that feel arbitrary or unfair.

This creates an interesting dynamic as traditional monetary systems show strain. When the dollar game becomes boring or unfun—when inflation makes saving pointless, when proximity to money creation determines winners more than productivity—alternatives become more appealing. The twenty million children who lived through Grow a Garden’s hyperinflation now understand this choice viscerally. They’ve experienced both functional and broken monetary games, and they intuitively know the difference.

The question isn’t whether Bitcoin will replace the dollar, but whether enough players will eventually find its game mechanics more compelling. My son’s generation may be uniquely positioned to make that judgment, having learned that all currencies are just games we agree to play—and that when games stop being fun, players find new ones.